Although

word form and meaning are logically distinct, there are several ways that form and

meaning can become correlated in language. When words have correlated form and

meaning for no obvious reason, we call them phonesthemes. The classic example

is the words beginning with gl that all have to do with a short

intense visual experience: glossy, glow, gleam, glisten, glitter, glitz, glint,

glow, glimmer, and glassy. Another example is the set of sl words that are associated

with a deficit in speed: slow, slump, slack, sluggish, slothful, sleepy, slumber,

slog, slouch, slovenly, and slack.

It turns

out there are many such pockets of arbitrary form-meaning correspondence,

especially if we loosen the criteria and look for words with related meanings that share a

letter sequence anywhere, instead of just at the beginning. For example, there

is another gl word associated with a short intense visual experience that no one ever mentions as part of the glitzy family: the word spangle. As another example, a lot of words semantically related to incarceration contain the bigram ai: along with the word

I’ve been

exploring this professionally a little and I will summarize my findings in another blog post

if those findings ever get through peer review. For now I just want to share some ‘found

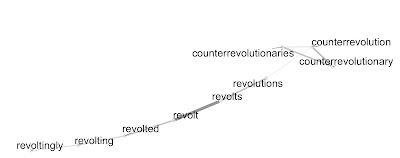

poems’ from my exploration. I created graphs that connected words that shared both form and meaning. Some elements of those connected graphs seemed to function almost as little

poems, so I have collected a few choice examples for you to enjoy (perhaps). I had a few arbitrary rules, of course, because everything is more fun with arbitrary rules. One rule was that I could erase connected words, but I could not add any. Another rule was that I could not change the location of any word networks, although it was arbitrary in the graphs I made: only networks that actually occurred together could be shown together.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The circle of worry

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––