Wednesday, 13 August 2014

On Having A Travel Plan

I did an interview about my novel on Deborah Kalb's book blog last week. One of the questions she asked was "Did you know how the novel would end before you started writing it, or did you make changes along the way?" This is my answer.

Imagine you are a young man taking a trip to Paris. You tell your best friend that you are going to spend time in Paris and he says: “Are you going to go up the Eiffel Tower?” and you say yes, you definitely will go up the Eiffel Tower. Being an organized guy, you even have a definite plan. The schedule you have made up for yourself says that you will go up the tower on your third day in Paris, just before you go to the Musée d’Orsay to see Manet’s famous painting of a nude women having a picnic with two formally dressed men, 'Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe'. But on your second evening in Paris, you find yourself in a little jazz bar that happens to be near your hotel, where you meet a wonderful woman with dark shiny eyes wearing too much bright red lipstick, who announces, after a couple of drinks and an intense and wonderful conversation, that you and she should take a train to Berlin together tomorrow to see an exhibition on the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși that just opened there. Because she is beautiful and you want an adventure and you are young and you love Brancusi too--and because that excess of bright red lipstick somehow just works on her, even though you had always thought you hated that look--you do go. So you end up spending time in Berlin rather than Paris, drinking German cocktails in dark German jazz cellars, and making love to a beautiful French woman in the reddish glow of a bedside lamp with a light silk scarf thrown over it, in a cheap hotel room that the two of you have decorated together by propping up postcards of works by Brancusi on every available horizontal surface. It is the best vacation of your life.

When you get home and your friend asks you how the Eiffel Tower was, at first you can hardly even understand what he is asking about. Your trip had nothing to do with the Eiffel Tower. It was about red lipstick and a beautiful bright-eyed French woman and Brancusi sculpture and Berlin jazz cellars.

Writing a novel is just like taking that trip to Paris.

Monday, 4 August 2014

On Where Pain Is

[Image from: Practical Observation of the Causes and Treatment of Curvatures of The Spine (1838), by Samuel Hare.]

"We must learn to suffer what we cannot evade; our life, like the harmony of the world, is composed of contrary things- of diverse tones, sweet and harsh, sharp and flat, sprightly and solemn: the musician who should only effect some of these, what would he be able to do? he must know how to make use of them all, and to mix them; and so we should mingle the goods and evils which are consubstantial with our life; our being cannot subsist without this mixture, and the one part is no less necessary to it than the other."

Michel de Montaigne / Of Experience

I was recently diagnosed with the syndrome of transverse myelitis, which is an inflammation of the white matter (which is white because it is covered by a fatty sheath called myelin) in the spine. It can be diagnosed with an MRI, which makes the (in my case, tiny) region of inflammation visible. The symptoms of myelitis are sensory and motor problems, including muscle cramping, muscle weakness, and an interesting variety of different flavors of pain. There is no cure but the symptoms usually disappear by themselves after a few months. "Touch wood", as my mother would say.

My own symptoms came on suddenly and were of bewildering variety. They eventually stabilized around two primary symptoms: left leg weakness and pain in various places on my right side, especially the sole of right foot, extending (in what seems like an unnecessarily ignoble touch) especially into my right small toe.

When I learned that that all this had been caused by a tiny speck of disorganized neural signalling, I was interested in the illusion that the pain that was caused by a lesion in my spine clearly felt like it was nearly a meter away, in my right foot. I began thinking about the question: What would we lose or gain if we said that the pain is actually in my spine, but it just feels like it is in my right foot?

One thing we lose is the generally inalienable right to ownership of our own phenomenology. If we cannot even tell where our own pain is, what are we?

One thing we gain, of course, is salvation of philosophical integrity. Typically a pain and the lesion that caused it are coincident in time and space. That is the whole point of the pain system.

We also gain a stark proof that pain is not even real, that it is ultimately just a signal running over an electrical line. Pain is being computed by a buggy program that will tell you the pain is a metre away from the lesion, in a part of the body that is in fact entirely uninjured.

It is after all easier to ignore static on your phone line than a laceration of your flesh.

Friday, 18 July 2014

On Considering Quivering Inequality As Passionate

Much to the hilarity of my teenage children, my mother still signs her letters 'LOL', meaning 'Lots Of Love'. Modern kids laugh at this because they know that LOL now means 'Laugh Out Loud'. They also know that an LOLCat is an Internet phenomenon, a photo of a cat overlain with bizarre or silly caption printed in a sans serif font. The LOLCats have now been generalized to LOLPics, which relax the limitation on only using pictures of cats.

JanusLOLs are a variation of LOLPics invented by Scottish PhD student and poet Calum Rodgers in 2013. He came up with the idea of using my nonsense-generator program JanusNode to generate the caption for a picture that is found by searching that caption on Google:

I have been collecting JanusLOLs on Pinterest here. Enjoy.

JanusLOLs are a variation of LOLPics invented by Scottish PhD student and poet Calum Rodgers in 2013. He came up with the idea of using my nonsense-generator program JanusNode to generate the caption for a picture that is found by searching that caption on Google:

"First, generate some language using JanusNode. Next, select a language string and use it as your search term on Google image search, then choose an image from the results page (extra points for using the first entry). Finally, upload the image to a meme maker and caption it using your selected language string."

I have been collecting JanusLOLs on Pinterest here. Enjoy.

Thursday, 26 June 2014

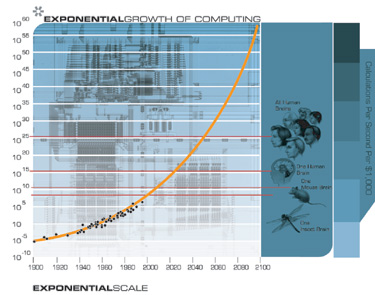

On the Processing Speed of the Human Brain

Many years ago a highschool student wrote to me asking for an estimate of the processing speed of the human brain. This is a difficult question to answer for many reasons.

One reason is that it is not easy to say how much information is carried by a single neural firing. Some people might say a single neural firing is equal to a single bit flip in a computer, which would be roughly equivalent to 1/64th or 1/128th of a floating point operation (FLOP). However, neurons are not strictly binary. Although it is true they either fire or don't fire, their firing represents the effect of much prior information and the summation of a variety of biochemical and computational factors. I think it is probably impossible to compute with any accuracy how much information is transmitted by a single neuron firing, since it would depend on a huge number of factors such as where the neuron is (in many senses: which species? Which part of the brain? Which individual?), what sort of neurotransmitters are implicated in the firing, how many neurons connect to that neurons, what kind and number of receptors that neuron has etc. However, I am willing to argue (guess) that these effects would almost certainly cancel out the fact that a FLOP involves 64 or 128 (or possibly more) bits, and therefore say it is probably OK, as rough measure, to say that a single neural firing is equivalent to a single FLOP.

With this 'settled', we can calculate the computing power of the human brain in FLOPs per second (FLOPS) because we have good estimates for the three main variables that enter into it: how many neurons (brain cells) we have, how fast a neuron can fire, and how many cells it connects to. A human being has about 100 billion brain cells. Although different neurons fire at different speeds, as a rough estimate it is reasonable to estimate that a neuron can fire about once every 5 milliseconds, or about 200 times a second. The number of cells each neuron is connected to also varies, but as a rough estimate it is reasonable to say that each neuron connects to 1000 other neurons- so every time a neuron fires, about 1000 other neurons get information about that firing. If we multiply all this out we get 100 billion neurons X 200 firings per second X 1000 connections per firing = 20 million billion calculations per second, which is 20 petaFLOPS.

This estimate might easily be off by at least an order of magnitude- that is, it might be at least 10 times too high or low. It also is a bit misleading because it estimates the raw 'clock speed' of the brain, which is much higher than the number of real useful calculations we do in a second. An apparently much simpler way to approach the problem is to note that the time it takes for the brain to make a really simple decision–like naming a picture or reading a word aloud–is about 300-700 milliseconds. So then we can say that brain can only make about two conscious calculations per second.

However, this is also misleading, for a bunch of reasons. One reason is that well-trained brains can make incredibly complex decisions that quickly. Moreover, even apparently simple tasks like reading a word aloud are actually extremely complex, actually requiring huge amounts of low-level computation. Finally, note that your brain is doing all sorts of things unconsciously at the same time (e.g. maintaining your body and its relation to the world) whenever you are engaged in conscious calculations. So depending on whether you want the raw clock speed, or some higher-level measure of information processing, the question has two answers that differ widely.

This estimate is the same as the estimate by the entrepreneur/futurist Ray Kurzweil (2 x 10^16 computations per second= 20 petaFLOPS). Kurzweil also predicts that we will achieve 20 petaFLOPS on a $1000 desktop PC by 2023. A top end desktop Mac Pro (admittedly, much more than $1000 today, alas) runs at 91 gigaFLOPS. To get to 20 petaFLOPS from 91 gigaFLOPS requires about 17.74 doublings. Computer speed doubles about every 18 months. 17.74 doublings x 1.5 years = 26.6 years. Kurzweil may be a little optimistic, but these calculations suggest that we should see human brain speeds in a desktop computer by 2041.

But doubling time is also decreasing, so Kurzweil may yet be right.

Saturday, 14 June 2014

On Why Duchamp Was Not A Dadaist

People often say that Duchamp was a Dadaist. He was not. He was already in New York in 1916 when Dadaism was being invented in Zurich, and by then had already completed many of the works that later got him associated with the Dadaist movement. He moved on the periphery of the movement and by his own testament had little to do with it. He once said of Dadaism that it "was parallel, if you wish" (in Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp). He made no attempt to ‘be a Dadaist’ when he moved back to Europe after World War I.

Duchamp also did not embrace the ‘pure meaninglessness’ of Dada. Dada was intended make thinking irrelevant by making it impossible. Duchamp’s work is intended to make the spectator think.

Saturday, 31 May 2014

On the Search for the Waters of Oblivion

Tuesday, 27 May 2014

On the Passage from Virgin to Bride

Duchamp's (1912) painting The Passage from Virgin to Bride (now at the MOMA in NYC) was one of his last paintings, the kind of art he would come to deride as 'retinal art'.

Although it is obviously very abstract, I think it actually looks fairly bride-like in miniature or from a distance, as this screen shot from Google search might make clear (I love the range of colors you get from doing a Google search for copies of 'the same image'):

Saturday, 17 May 2014

On Typographically Interpreting The Bald Soprano

I love Massin's typographic version of French-Romanian playwright Eugene Ionesco's amusing and absurd play The Bald Soprano.

Sunday, 11 May 2014

On a Penchant for Activities in the Pop Dada Vein

Following on from Jaap Blonk's recital of German Dadaist Kurt Schwitters' nonsense poem Ursonate (and as kind of a pop-culture equivalent), I really enjoy this take by Italian singer/comedian Adriano Celentano on what American English sounds like.

Thursday, 8 May 2014

On a Penchant for Activities in the Dada Vein

I appreciate Dutch performer Jaap Blonk's technologically-enhanced performance from memory of German Dadaist Kurt Schwitters' nonsense poem Ursonate, which Schwitters developed over many years starting in 1925.

I also enjoy this description from the BBC website of Jaap Blonk:

-

"His unfinished studies in physics, mathematics and musicology mainly created a penchant for activities in the Dada vein, as did several unsuccessful jobs in offices and other well organised [sic] systems."

Monday, 28 April 2014

On The 296,613 Anagrams of 'Philadelphia Freedom'

In Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll famously left a riddle unanswered: Why is a raven like a writing desk?

"Have you guessed the riddle yet?" the Hatter said, turning to Alice again.In a later edition Carroll offered an answer: Because it can produce a few notes, tho they are very flat; and it is nevar put with the wrong end in front! Alas, a humorless copy editor ruined the best part of that joke by changing 'nevar' to 'never' before the edition was published, so the answer was never published as intended.

"No, I give it up," Alice replied. "What's the answer?"

"I haven't the slightest idea," said the Hatter.

"Nor I," said the March Hare.

Alice sighed wearily. "I think you might do something better with the time," she said, "than wasting it in asking riddles that have no answers."

Another excellent answer was offered by 'puzzle maven' Sam Lloyd in 1914 (according to Cecil Adams' The Straight Dope): Because Poe wrote on both.

In my own novel, The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even, there is a similar unanswered riddle. As the three main characters complete the first half of their road trip from Medford, MA by driving into Philadelphia, PA, one of them, Greg, plays Elton John's song Philadelphia Freedom. He asks the others: For ten points, and today’s grand prize, who can tell me what that song has to do with Duchamp? The chapter ends there; no answer is ever given.

Greg is obsessed with anagrams, for reasons that are partly to do with Duchamp, who greatly enjoyed anagrams and other wordplay. I asked my son to write me an anagram-finding computer program that could deal with long strings, which most on-line anagram tools cannot. There are at least 671 English words contained inside the string Philadelphia Freedom, and my son's program found 296,613 anagrams that used all the letters. I wrote my own computer program to help conduct a systematic search through this set, looking for an anagram that might serve as an answer to Greg's riddle. I found several candidates, but my son and I selected this one as our favorite:

LIMP? HAHA! DID LOPE FREE!

Duchamp's life can be seen a celebration of freedom, as a throwing off of all limitations. He never limped along but rather ran freely: i.e. he DID LOPE FREE.

[Image from: http://ellelirie.blogspot.ca/2012_07_01_archive.html]

Friday, 18 April 2014

On Caravaggio As (Like Duchamp) An Artist of Time

Sunday, 13 April 2014

On Samuel Beckett's Birthday

Although today, April 13th, is indisputably my own birthday (thanks for your congratulations), it might not actually be Samuel Beckett's birthday, despite what you may have read on your Twitter account or elsewhere today. It pleased Samuel Beckett to believe that he was born on a Friday that was simultaneously Good Friday and Friday the 13th: April 13th, 1906.

However, according to his biographer Anthony Cronin, Beckett's birth certificate indicates that he was born a month too late for such an auspicious entry into the world, on Sunday May 13th, 1906, with the birth being registered four weeks later, in June, as was customary. Of course, it might be an error on the birth certificate. The matter remains uncertain. In his biography Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist Cronin writes "Since Beckett was on the whole truthful about such matters and on at least one occasion claimed to have the authority of his mother for the Good Friday birth-date, the balance of probability is in its favour, but it is a pity nevertheless that there should be any doubt about it."

[Image: Samuel Beckett at Riverside Studios (1984), a lithograph by Tom Phillips that is in the collection of England's National Portrait Gallery. The words are from Beckett's Worstward Ho, and have been adopted as a personal motto both by Phillips and by me.]

Monday, 31 March 2014

On Free Books

I'm giving away five free copies of my novel on GoodReads.com. Details below.

Enter to win

Goodreads Book Giveaway

The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even

by Chris F. Westbury

Giveaway ends June 10, 2014.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

Saturday, 29 March 2014

On the Final Cover of my Novel

My novel The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even went to press yesterday. Here is the final cover, designed by Michael Kellner. I love the design: it captures the quirky, off-beat feel of the story and pays homage to Duchamp in many different ways.

The excerpt on the back is the following:

-

“It didn’t take me long to make friends with the

museum guard, a muscular young red-haired Irish

Bostonian named Bobby Sheridan. He sussed me out on

my first vigil in front of the ivory carving. After

I had been sitting in front of it for about an hour

he came over to ask me if I was OK. I told him I

was fine, very well actually, except for having a

minor mental illness. I explained to him that I had

obsessive compulsive disorder and couldn’t touch

anything, and also that I didn’t have to work because

my mother had died and I had inherited some money,

enough to live for a while on but not really a lot.

I explained to him that I was planning to spend many

months in his museum, not touching anything of course

but mainly just looking at a particular single piece

of art, namely the carving of Abraham and Isaac that

was in front of me. And I also let him know that I

always wore pretty much the same clothes but that I

changed my clothes and had a shower every day, and

that I was very careful about cleanliness as part of

my OCD. I drew his attention to some of the things

I appreciated so much about the ivory

carving, especially the ample bosom

and translucent wings of the

tiny angel.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)